Ten years ago, Boeing stopped offering its Gold Standard pension plan, which pays retirees a guaranteed amount. The loss of pensions still angers many members of the company’s largest union.

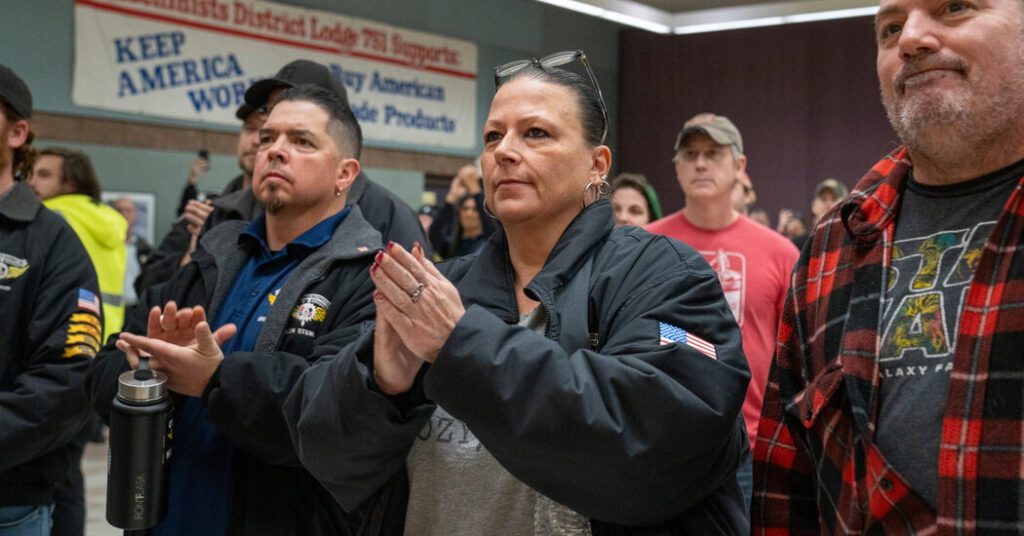

On Wednesday, union members voted to reject an improved contract proposal from management, primarily because the agreement would not restore pensions. The vote will extend a five-week strike and derail the jet maker’s efforts to recover from a years-long crisis.

Severance benefits are the biggest stalemate between Boeing and its employees after the company has largely met union demands in other areas, including offering a nearly 40% pay increase over the course of a new four-year contract. This has become a bottleneck.

Retirement and labor experts say it may be difficult to reach a compromise on this issue. That’s because Boeing is unlikely to want to incur the much higher costs of a traditional defined benefit pension plan compared to the defined contribution plans that are standard at many U.S. companies. Members of the union, the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, also appear determined not to back down on their demands for expanded retirement security.

John Holden, president of the union District 751, which represents the majority of workers, said Wednesday after 64% of voters rejected the proposal, “All workers are entitled to a defined benefit pension. I believe there is,” he said. “It wasn’t right to take it away. It’s the right fight to try to get it back.”

Boeing has previously said it has no intention of reinstating its pension plan, which was frozen in 2014. “Pension plans are prohibitively expensive, which is why virtually all private employers are opting out of them,” the company said in a statement last month. – Benefit pension plan.

The aerospace manufacturer did not comment on Wednesday’s vote other than to say it was “disappointed” with the result.

Like most large American companies, Boeing currently offers a 401(k) plan with no guaranteed payments. Additionally, these plans rely heavily on employee contributions, which may leave employees unable to afford to set aside sufficient funds, ultimately reducing their retirement income. Companies often match a certain portion of the funds contributed by workers, effectively placing limits on how much they can spend on retirement benefits.

Boeing executives expect their stance on pensions to soften, even though they want the strike to end so they can focus on repairing the company’s reputation after two fatal crashes and weak financial results nearly five years ago. Few labor experts do.

“I don’t think Boeing will come back,” said Harry Katz, a professor at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations, noting that the company is focused on controlling costs to regain Wall Street’s confidence.

Most investors are likely to oppose reinstating the defined benefit pension plan, as such a plan could hurt Boeing’s financial position. Bank of America equity analysts estimate that offering such a plan would cost Boeing an average of $300 million to $400 million more annually than its 401(k) plan.

Defined benefit pensions reached their peak in the 1970s. According to the Employee Benefit Research Institute, an independent organization that tracks retirement issues, nearly 62% of private sector workers who had access to workplace plans received only defined benefit pensions at the time.

Companies began moving away from pensions in favor of 401(k) plans in the early 1980s. These new plans were easier to administer and cheaper because companies only had to pay a portion of the plan contributions. Unlike defined benefit plans, 401(k) plans don’t obligate companies to put in additional funds if they don’t generate enough income to pay contributions to retirees.

The institute’s research shows that by 2021, only 1% of workers enrolled in their employer’s plan will have access to only a defined benefit plan, and 84% will only have access to a 401(k); 15% said they had access to both.

At the beginning of this century, after the tech bubble burst and interest rates fell, many pension funds became severely underfunded. In 2006, stricter funding and accounting rules were applied. According to the Center for Retirement Research, these changes made defined benefit plans even less attractive to companies by forcing them to put more money into defined benefit plans and recognize pension obligations as liabilities. .

As a result, private pensions began to disappear even faster. Employers closed plans to new workers, froze benefits for those already enrolled, and began reducing debt.

In an infamous deal that remains in the memory of many Boeing mechanics, the company’s union leaders in 2014 cut off defined benefit pension payments to new employees and froze benefits for existing employees. We agreed.

Ahead of the deal, Boeing indicated it might move production of the new plane out of the Seattle area, where many of its mechanics live. Union leaders believed a compromise on pensions was necessary to prevent Boeing from moving to states with labor laws that favor employers over unions. However, much of the public believed that the company would not have been able to successfully survive the threat to move large amounts of production elsewhere. (Boeing has a non-union factory in South Carolina where it builds the 787 Dreamliner.)

“We swore we would never be put in a position of no influence,” Holden said of the 2014 events in a September interview.

According to Boeing, 42% of IAM members still participate in defined benefit plans. Among the rejected proposals, the company proposed increasing payments from pensions. Under the proposal, workers with 20 years of eligible employment under the plan would receive a monthly pension of about $2,100, up from $1,900.

Holden said Wednesday that while few labor experts expect machine workers to secure the return of their defined benefit pensions, it’s possible the company and union could reach some kind of agreement on severance pay.

He said Boeing was not making “sufficient efforts in other ways” to persuade member states to abandon demands to reinstate frozen pension plans. And Holden said it intended to look at “other defined benefit options” and “be creative and see what we can do to give our members what they deserve.”

It’s not clear exactly what Boeing can offer that will satisfy the majority of the machinists’ union. Retirement experts say there are several options, all of which involve tradeoffs.

Boeing may increase contributions to its 401(k) plan. The rejected proposal proposed a $5,000 one-time contribution to 401(k)s, making 100 percent of an employee’s contribution equal to the first 8 percent of the employee’s salary, up from 75 percent. . Boeing already contributes 4% of wages, whether employees contribute or not.

Retirement experts say one option Boeing and the union could consider is a cash balance plan. These plans promise a fixed account balance rather than a guaranteed lifetime paycheck based on a specific formula. Workers typically earn a percentage of their salary plus interest that tracks a benchmark, based on a plan for each period of employment.

Holden said: “There are other hybrid plans that we have considered, so we can’t say no to anything that offers clear benefits to our members.”

IAM did not respond to an email requesting details about the severance pay request.

Alicia Munnell, director of Boston University’s Retirement Research Center, said labor and management will ultimately need to distribute “a pot of gold” in wages, retirement plans and other benefits.

“So if workers want more compensation, cash wages may not be a bad way to resolve this conflict,” Manel said. “If the problem is really more symbolic, I think the alternative could be a cash balance plan, a defined benefit plan to be precise.”

She said these plans have certain advantages because they are easier to carry than traditional pensions and participants can choose to receive fixed benefits after retirement.

Niraj Chokshi contributed reporting.