A post-pandemic surge in vacancies and debt service has devoured commercial real estate for more than two years. Even as that threat begins to fade, owners of shopping malls, apartment buildings and office towers face a potentially long-term problem of rising insurance premiums.

This problem is well known to homeowners across the country. The rise in climate-related natural disasters is causing insurance companies to significantly increase premiums or exit the market. Insurance premium increases have been most rapid in coastal cities and towns, which are more susceptible to damage from major storms and coastal flooding, but insurers and banks are increasingly facing extreme and unpredictable weather events. People are coming to terms with the idea that no area is truly safe.

Hurricane Helen, which hit Florida’s Gulf Coast, left a trail of deadly flooding and mudslides across Georgia and the western Carolinas, but in the process cost the economy at least $35 billion, according to estimates from reinsurance broker Gallagher. It is likely that this caused the loss. Re.

Building owners are also caught between insurance companies and lenders, who fear catastrophic damage and offer even the most breathing room to struggling renters. Even small changes to the insurance contract are not allowed.

It’s impossible to know comprehensively how many properties have been foreclosed on solely because of insurance costs, but industry insiders say they are aware of deals that have fallen apart over the issue. Developers and investors say insurance costs could tip the balance in an industry facing rising interest rates and rising costs for materials and labor.

“The current interest rate environment exposes the divide between those who know what they’re doing and those who don’t,” said Fundamental, a New York-based investor with $3.5 billion in assets.・Mario Kilifersky, head of asset management at Advisors, said: .

Insurance brokerage firm Marsh McLennan estimates that commercial real estate insurance premiums rose an average of 11% last year nationwide, but up to 50% in storm-prone areas like the Gulf Coast and California. Insurance premiums may have doubled in some places this year, according to brokerages.

Insurance premiums now account for 8% of operating costs for multifamily properties, double the amount it did about five years ago, said Paul Fiorilla, director of research at data provider Yardi Matrix. . Fiorilla said insurance is still only a small piece of the pie compared to expenses such as taxes and maintenance fees, but stagnant rents and rising borrowing costs are adding to the burden. He said operating expenses for landlords increased faster than revenue last year.

Lenders are worried.

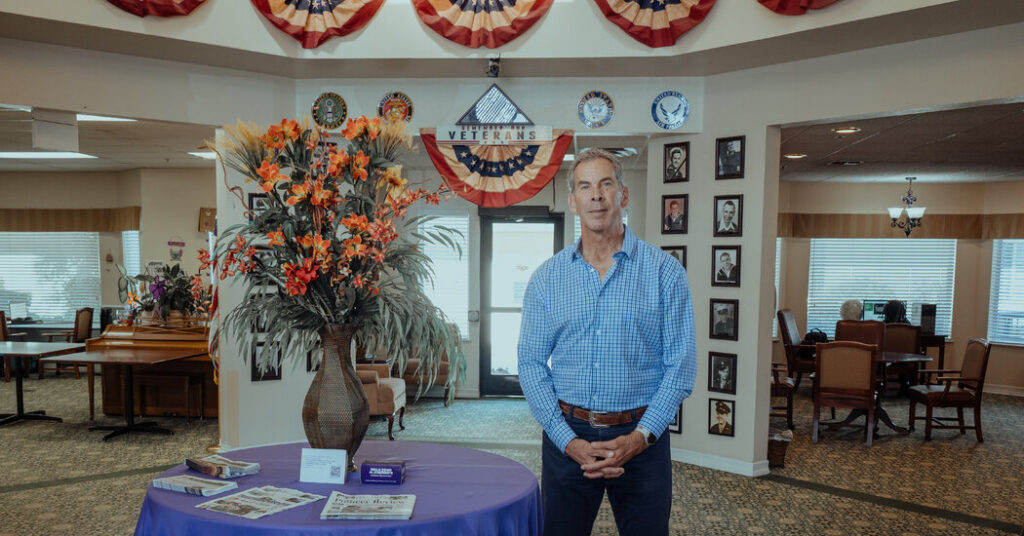

“We’re constantly hearing from banks,” said Titan Real Estate Investments, a California-based owner of senior living facilities and cold storage warehouses that store fruits and vegetables. said Kevin Kasseff, co-founder and managing partner of the group. For supermarkets.

Karsev said lenders are asking for details on how they receive insurance, and some insurers have stopped new business, especially for buildings in California.

“They’re nervous,” he said, frustrated that lenders seemed eager to hear about his latest plans but showed no desire to help. he added.

Just like homeowners, commercial property owners are required by banks to carry insurance if they have a mortgage. However, the requirements can be more stringent. Commercial real estate borrowers often require explicit permission from their lender to adjust insurance coverage, but if the loan is securitized and sold to Wall Street investors, It may be impossible to obtain that permission.

Lenders have largely refused to ease insurance requirements, fearing the potential impact on the broader real estate market. What happens if a catastrophe destroys a building and no one can afford to rebuild it?

“Insurance pricing is stopping deals and, in some cases, forcing deals into foreclosure,” said Daniel Lombardo, head of real estate, hospitality and leisure at insurance broker Willis Towers Watson. Ta. Part of the problem, she said, is that costs can jump from the time a buyer begins financing to the moment the deal closes.

For Karsev, the solution seems simple. Banks should require commercial property owners to purchase high-deductible insurance to reduce coverage costs. Alternatively, they should approve a policy that compensates only the amount of a bank loan, not the cost of rebuilding a building if it is destroyed.

But Adam DeSanctis, a spokesman for the Mortgage Bankers Association, said if uninsured homeowners are unable to rebuild after a catastrophe, the real estate market could become unstable and the value of banks’ collateral could be eroded. He said that banks may not be willing to act because of the Industry organizations. Regulators are also closely watching how banks respond to avoid increasing risks to the financial system.

Mr. Kiliferski, whose Fundamental company owns apartments and other properties in Houston, Corpus Christi, Texas, and elsewhere, said his company forgoed some exterior upgrades to save on insurance costs.

For example, instead of adding flashy decorations and appliances to the apartment complexes Fundamental purchased in Corpus Christi, the company will overhaul the building’s energy use to reduce the cost of electricity and other utilities. It is said that

“We were going to renovate these units by installing stone countertops and backsplash lights,” Kirifalski said. “We are now rethinking how we spend that money.”

Analysts say insurance problems are more of a headache than a potential catastrophe, and data on loan delinquencies shows stress but not enough to cause major alarm. Banks could have avoided the crisis by being more careful with their lending and keeping as many old commercial real estate loans off their books as possible.

Delinquencies have increased to 1.5% of commercial real estate loan balances since fall 2022, said Nathan Stovall, director of financial institutions research at S&P Global Market Intelligence. The largest banks reported the largest increase in delinquency rates at 5%. This is still far from the 10% level seen during the 2008 global financial crisis.

Stovall said large banks’ loans include buildings such as high-rises in urban areas where office workers have not returned and are most affected by changes in occupancy patterns that began with the pandemic, so commercial real estate “The downturn in the economy is hitting major banks even harder,” he said.

On Sept. 18, the Fed cut its benchmark interest rate by 0.5 percentage point, the first reduction since rates spiked in 2022 and 2023, with further cuts expected this year and next.

This is the first good news for commercial property owners in years, but it doesn’t mean developers are out of the woods. Interest rates are much higher than the last time many borrowers took out loans for real estate (which many did when pandemic-induced interest rates were at rock bottom). And finding new financing is difficult.

Mr. DeSanctis, a banking industry representative, and Mr. Lombardo, an insurance broker, said handling insurance used to be left to middle managers, who didn’t bother executives with details. . But that has changed.

The small annual conference hosted by Mr. DeSanctis’ industry group, which once attracted only about 100 people with the strict title of “risk manager,” has become increasingly popular in high-stakes property and casualty insurance. He said the company has doubled in size to cope with the pursuit. It is now a broader strategy meeting attended by people who make lending decisions and those in senior management positions.

DeSanctis said mortgage bankers need to consider risks that previously seemed too far away to worry about, especially given the damage Hurricane Helen caused far from the coast. Ta.

“It needs further analysis,” he said.