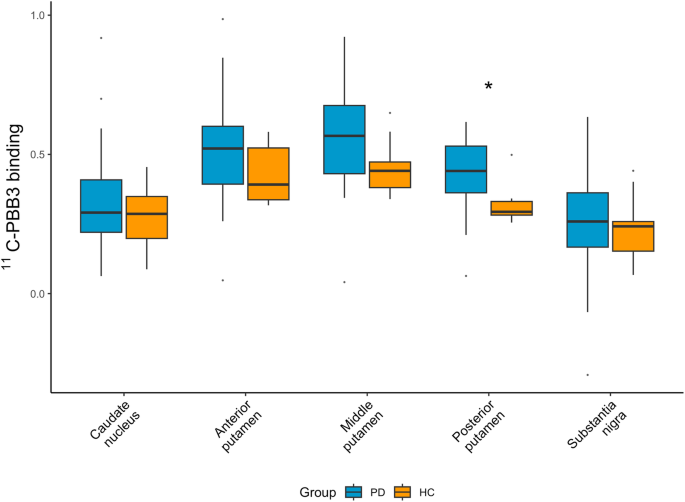

Our data show increased (11C)PBB3 binding in bilateral posterior putamen of PD patients. Based on previous in vivo6 and post-mortem7 findings, we believe this likely reflects a relatively greater neuropathological burden of abnormal protein aggregation at this level in PD. We did not find significant increases in other regions of the striatum, nor in the substantia nigra. These findings are compatible with the hypothesis that striatal nerve terminals are the main target of misfolded proteins in PD8. Of note, on the assumption (see below) that (11C)PBB3 may bind to misfolded α-syn in addition to tau, at least some of the (11C)PBB3 binding detected could be due to extraneuronal α-syn, which has been demonstrated in several brain regions in PD, including the striatum. This is particularly relevant because most dopaminergic striatal innervation has disappeared at the point the scans were taken9. We did not find a correlation of (11C)PBB3 BPND with either disease duration or the degree of dopaminergic denervation in any of the nigrostriatal ROIs. We believe this may reflect a combination of abnormal protein deposition, counterbalanced by progressive neuronal loss. Indeed, these in vivo imaging data are supported by the demonstration of early increases in aggregated α-syn in the putamen of patients with minimal motor features and suspected prodromal PD, who show greater striatal LN pathology than advanced PD, suggesting early involvement of nerve terminals10. Despite PD frequently manifesting as an asymmetric condition and the asymmetrical pattern of dopamine denervation, the asymmetry of other neuropathological features, such as protein aggregation, has not been documented, and therefore, the lack of asymmetric (11C)PBB3 uptake in the putamen of patients with PD of moderate disease duration may not be entirely surprising. Nevertheless, we did observe a trend towards higher values on the more affected side, with non-significant higher median values in both putamen (anterior, middle, posterior and whole) and SN. This difference between sides is small in magnitude and the variance is high, but this trend suggests the need for further investigation to elucidate the potential asymmetrical involvement of neuropathological features in PD beyond dopamine denervation.

The site of initial protein aggregation and neurodegeneration within the nigrostriatal pathway is unknown. However, in the widely held theory of stereotypic caudal-to-rostral disease progression, the SN is thought to be affected prior to subsequent loss of striatal terminals2. Indeed, a recent modification of this hypothesis does not consider the role of pathology starting in striatal nerve terminals11,12. Alternative hypotheses are based on several relevant findings. First, the motor manifestations of PD almost always show an asymmetrical focal onset and a somatotopic pattern of spread; therefore, it would be logical to think that the brain region of initial involvement might also have a somatotopic organization. The lack of known SN somatotopy in humans as well as in other primates13 and the diffuse axonal arborization of the nigrostriatal neurons in the striatum, where a selective pattern of denervation is observed, cannot explain the focality of the clinical findings. In contrast, other PD-relevant structures such as the putamen and motor cortex do show somatotopic organization14, and therefore represent potential candidate locations where neurodegeneration may begin. Secondly, axonal transport dysfunction has been shown to represent an early and crucial pathological mechanism in PD, and may precede degeneration15,16. This finding has also been reproduced in vitro in rat cultured neurons transfected with plasmids containing human mutant α-syn, suggesting a critical role in perikaryal accumulation of α-syn17. Indeed, axonal transport defects are seen only in those PD nigral neurons that contain Lewy pathology, while adjacent neurons without Lewy pathology demonstrate normal levels of axonal transport motors, findings that are duplicated in synuclein-based PD models16. Thirdly, α-syn is physiologically located mainly in axonal terminals, and therefore it is likely that the pathogenic changes and aggregation start at this level, as indeed supported by the observations that LN precede the appearance of LB in most affected brain structures in PD2. In the peripheral nervous system, the axonal aggregation of α-syn is more abundant and precedes the involvement of ganglia, suggesting a centripetal axon-to-soma progression18. Also, in non-human primate models, α-syn is transported from axon terminals to neuronal bodies, with LB-like aggregation in the SN following intraputaminal α-syn injection19, and selective increase of α-syn in the posterior putamen following enteric injection of PD-derived α-syn, supporting the relevance of posterior putamen as a key target for α-syn pathology20. Finally, both neuropathological and molecular imaging evidence have shown that at the time of diagnosis the striatal axonal loss exceeds neuronal loss in the SN, supporting the early involvement of striatal terminals in the pathophysiology of PD9,21,22. Interestingly, the bottom-up and top-down hypotheses may not be exclusionary, and there might be a different pattern of progression in different phenotypes of PD patients.

Off-target binding to monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) has been demonstrated for several tau tracers23. MAO-B is mostly located in glial cells, and its expression in reactive astrocytes has been shown in several diseases24. To date there is no evidence of PBB3 binding to MAO. Nevertheless, we scanned a subset of PD patients with (11C)PBR28, a marker of microglial activation, and found no relationship to (11C)PBB3 binding in those regions with increased PBB3 binding, consistent with a lack of off-target binding to MAO. Of note, the within-individual Spearman rho correlation coefficient between the ranked binding of the two tracers across different brain regions decreased significantly with increased disease duration. While based on a very limited number of subjects, this suggests that the two neuropathological processes (i.e., neuroinflammation and protein aggregation) might occur in parallel in the early stages of the disease, but less so when disease is more advanced. Previous pre-clinical studies have shown that abnormal protein deposits may have a pro-inflammatory effect in PD25,26, while other studies have provided evidence of microglial activation promoting protein aggregation27, suggesting a complex interplay between protein aggregation and inflammation. Future studies investigating the longitudinal progression of neuroinflammation in different brain regions in PD will provide further insights into its role in neurodegeneration and its neurobiological relationship with dopamine denervation and protein aggregation.

As noted above, unlike other 1st generation tau PET ligands, (11C)PBB3 is not thought to bind to MAO and this is in keeping with the overall lack of relationship to (11C)PBR28 binding in the current study. The binding of (11C)PBB3 to misfolded tau has been extensively characterized both in vitro and in vivo and is shown to bind to both 3R/4R and 4R tau pathology6,28,29. Both post-mortem7 and in vivo6 studies suggest that PBB3 binds as well to α-syn, although the degree to which the (11C) tracer does so in conditions of relatively low target availability is unclear. In favor of the hypothesis that (11C)PBB3 binding we observe here is to α-syn and not tau is the fact that 2nd generation tau tracers (18F)PI-262030 and (11C)florzolotau31 do not show significant uptake in patients with PD compared to HC. These tracers were not available at the time this study was conducted. There was uptake of (18F)-AV1451 in the putamen of PD patients in a recent study, but this was attributed by the authors to off-target binding32. However, even if elevated (11C)PBB3 is indeed representative of tau binding, this might not be surprising in view of recent evidence for early tau pathology in the nigrostriatal system of subjects with mild motor deficits insufficient to be diagnosed with PD, even without α-syn aggregates33, nor would this possibility have any impact on our interpretation that the pathology of PD starts in nerve terminals.

Although it did not reach statistical significance following correction for multiple comparisons, (11C)PBB3 binding in the hippocampus and parahippocamal/entorhinal regions showed a nominal increase in binding in PD participants. Interestingly, these regions are affected early by LP, and are known to show β-amyloid and tau aggregation later in the progression of the disease2. More specifically, LN are abundant in the anteromedial temporal mesocortex from early stages of the disease as this represents one of the first affected sites in the cortex.

Both α-syn and tau are increased in cortical regions in PD-related cognitive impairment. Anterior cingulate, temporal, and entorhinal cortex have often been implicated as some of the primary areas affected in PD-related dementia and where pathology is negatively correlated with cognitive outcomes34,35. Our data mirror these neuropathological studies, with increased (11C)PBB3 binding in CI-PD in the anterior cingulate, where we also found a negative correlation with the cognitive outcome, despite a relatively large number of missing DRS-2 scores in the CI-PD population. Previous neuropathological studies have shown that different misfolded protein deposits follow patterned topographical distributions in the brains of people with PD, with α-syn being more abundant in the cingulate cortex, while pathology in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex is mixed, with higher concentration of neurofibrillary tangles35. Consistent with this, the region most significantly related to cognitive impairment in this study was the anterior cingulate, favouring the hypothesis that, in this subject population, increased anterior cingulate (11C)PBB3 binding may be due to α-syn pathology, while in other regions it could represent mixed or tau aggregation. Interestingly, there was a nominal trend towards increased binding in the entorhinal/parahippocampal cortex (nominal p = 0.011), middle frontal gyrus (nominal p = 0.030), occipital cortex (nominal p = 0.041), subcallosal gyrus (nominal p = 0.041) and amygdala (nominal p = 0.047) in CI-PD vs. HC, but these differences did not survive multiple comparison correction. We believe that an increased sample size would allow the detection of more regions with increased protein load in the setting of CI-PD. In further support of our view that PBB3 binding in anterior cingulate reflects binding to α-syn rather than tau pathology, a recent study with (18F)AV1451 failed to demonstrate binding in the cingulate cortex of PD patients at high risk of dementia32.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the signal-to-noise ratio of (11C)PBB3 is not ideal, which may reduce the likelihood of finding significant results. Despite that and the relatively small sample size, we found statistically significant differences, with high biological coherence and relevance. The sample size was limited by challenges with recruitment, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as difficulty with tracer production. Logistical challenges as well as limited access to tracer (which has a short half-life) meant that the study was conducted in a single center. It is possible that some comparisons that failed to be statistically significant when corrected for multiple tests would have been significant with higher sample size or if the tracer were more sensitive. The (11C)PBR28 PET sample size was even smaller, and therefore the results should be interpreted with caution. A number of CI-PD participants did not complete the DRS-2 (n = 6/13), this might have had an impact on the correlation analysis, more likely reducing the statistical power to find other potential relationships that did not reach statistical significance. Secondly, disease-related atrophy of the basal ganglia and cortex may artefactually reduce the BPND in PD. To limit the impact of this artifact, we used partial-volume correction, which should at least partly address this issue.

As discussed above, (11C)PBB3 may bind to α-syn deposits in addition to the known tau affinity. While lack of selectivity is often not ideal for a molecular imaging tracer, it may be advantageous in this situation, as it may allow the detection of abnormal aggregation of either protein, especially considering that tracers selectively binding to α-syn are not currently available. It is indeed possible that the binding shown in the present study is related to α-syn in some regions and to tau in others. In the case of the putamen, the absence of significant binding increase in CN-PD patients with other tau tracers, including the fluorinated derivative of (11C)PBB3, (18F)PM-PBB336, which has a higher tau selectivity and higher signal-to-noise ratio, lends support to our interpretation that our findings reflect α-syn rather than tau binding, although this should be confirmed in further studies. Nevertheless, a tracer with higher specificity to α-syn remains desirable. Indeed, a tracer with higher selectivity and signal-to-noise ratio would represent a major step-forward as a biomarker in the setting of clinical trials for disease-modifying therapies in PD. Recently identified derivatives of PBB3 and other compounds have shown higher α-syn selectivity in vitro and in vivo in animal models37,38, and show increased binding in MSA patients, in brain areas known to have high α-syn load39, but with limited binding in PD40.

Our findings demonstrate increased protein aggregation in vivo in the posterior putamen of PD patients, that may at least partially reflect α-syn pathology. The greater increases in nigrostriatal nerve terminals and other locations selectively affected by non-LB α-syn aggregation support the theory that the disease affects nerve terminals preferentially, rather than neuronal bodies. Our findings also support the role of protein misfolding in the anterior cingulate as an important determinant of cognitive function in PD.