CCC mineralogy and petrography

All samples consist of calcite. This also applies to two samples transported in cold condition to the laboratory and examined by XRD (see Methods). No evidence of precursor phases such as ikaite was found.

Under the microscope the samples are composed of > 99% euhedral calcite crystals and aggregates thereof. Granulometric measurements show median grain sizes between 44 and 199 µm (Table 1). The crystals show a homogeneous whitish color in reflected light. Impurities, i.e., detrital grains derived from the host limestone, are rare and easy to recognize based on their color (commonly light red to yellow) and anhedral shape.

Table 1 Grain size, radiocarbon and stable isotope data of CCC samples from Mörkgletscher (arranged according to depth, where 0 cm is the base of the ice in a drill core 1.9 m below the ice floor), as well as of two samples of experimentally formed CCC from Eispalast (L1-1, L2-2) and two CCC samples from Eispalast (F320) and Eistunnel (ETB).

Optical microscopy and SEM observations revealed a range of particle shapes. The most abundant type are crystal aggregates showing a radial arrangement of intergrown crystals (Fig. 3). These aggregates are often asymmetrical in structure and show a conspicuously flat upper side and a lower side covered with crystal tips. The upper side sometimes shows holes with a diameter of 5–15 µm. The second most abundant type are skeletal crystals or skeletal crystal aggregates. These show a very high microporosity. There are all transitions from crystal aggregates to skeletal crystals. Finally, there are (hemi)spherulitic aggregates showing a concentric shell structure. These particles often have a flat upper surface and are partly porous.

Figure 3

Microscopic appearance of fine CCC from Mörkgletscher. (a) and (b) are optical images of aggregates of euhedral calcite crystals showing a variety of particle shapes. (c) and (d) are SEM images of rafts and spheroids, respectively, both characterized by a conspicuously flat side where these particles touched the ice during growth.

CCC stable isotope composition

Fine CCC from Mörkgletscher are characterized by highly positive δ13C values and moderately negative δ18O values (Fig. 4, Table 1). δ13C values reach as high as + 13.5‰. Aliquots measured of each CCC sample commonly show a tight clustering with only a few tenths of permil variability in both C and O isotopes; a few samples yielded a slightly larger variability of up to about 1.5‰ in δ13C and up to about 0.5‰ in δ18O. The C and O isotope data are linearly correlated (r2 = 0.52) with a positive slope of 0.83 (Fig. 4). These isotopic values are distinct from both calcite derived from weathering of the host rock limestone and from coarse grained CCC which are present in interior (and currently ice-free) parts of this cave and which document episodes of much more extensive cave glaciations prior to the Holocene (ref.32 and unpublished data by the authors).

Figure 4

Carbon and oxygen isotopic composition of fine CCC from Mörkgletscher (n = 66) compared to Dachstein limestone (n = 38), the host rock of the cave (host rock data31). Also shown is the stable isotopic composition of coarse grained CCC from inner and currently ice-free parts of Eisriesenwelt (unpublished data by the authors).

Radiocarbon results

15 CCC samples from Mörkgletscher were analyzed for radiocarbon and the resulting conventional ages range from 921 to 3517 BP (Table 1). There is no relationship between 14C ages and δ13C values (r2 = 0.0002) suggesting that there is no significant detrital contamination by radiocarbon-free host rock particles characterized by much lower δ13C values (Fig. 4). Replicates of samples from three CCC layers yielded conventional ages that agree within 4.4, 7.0 and 9.0% and two samples taken laterally within one CCC layer deviate by 12% (Table 1). Plotted against depth, the conventional ages decrease from the bottom of the ice section up, with the uppermost samples being approximately 2000–2500 14C years younger than the deepest ones (Fig. 5).

Figure 5

Conventional radiocarbon ages of fine CCC from the Mörkgletscher ice cliff plotted against ice thickness. The analytical uncertainty of the measurements is well within the size of the symbols. Black arrows indicate CCC layers where duplicate samples were analyzed. The green arrow marks two samples taken laterally within a CCC layer.

DIC of a sample (ERW-B) taken from the water coming from the Alphorn shaft yielded 95.2 ± 0.5% pmC, which indicates a low dead carbon effect (4.8%) and a small reservoir age (395 ± 42 14C yr). CCC formed experimentally in small pools in Eispalast33 yielded conventional radiocarbon ages of 356 ± 20 BP (sample L1-1, using water from the Alphorn shaft) and 511 ± 19 BP (samples L2-2, using water from the Elefant site—Fig. 1, Table 1).

230Th results

Three CCC samples were analyzed for 230Th. Sample M-G1 from near the top of the ice section yielded an age of 953 ± 303 yr BP. Sample M-A20 from the lower part of the cliff and sample M-E154-156 taken from a drill core at the foot of the cliff yielded ages of 2262 ± 4346 and 3737 ± 1954 yr BP, respectively, which are in stratigraphic order but very imprecise due to the large Th correction (Table 2).

Table 2 230Th ages of CCC samples from Mörkgletscher.

Origin of the CCC layers and the ice cliff

Several lines of observations show that the discontinuous “dust layers” at Mörkgletscher are deposits of fine CCC with only tiny traces of other, i.e., detrital (limestone) particles. These observations include the euhedral shape and the stable isotopic composition of these carbonate crystals and crystal aggregates. The stable isotopic composition is not only distinct from that of the local limestone, but also consistent with fine CCC extracted from an ice core drilled in the Eispalast20 and fine CCC found on top of modern ice surfaces in this cave (unpublished data by the authors). The C isotope values overlap with fine CCC from ice caves in Romania34 and the Canadian Arctic35, but the O isotope values are shifted towards higher (Romania) and lower values (Canada), reflecting the overall δ18O values of meteoric precipitation (higher and lower in Romania and Canada, respectively). These data suggest fairly rapid crystallization from a thin water film on ice surfaces. The abundance of skeletal crystals and spheroidal forms is consistent with this mode of formation.

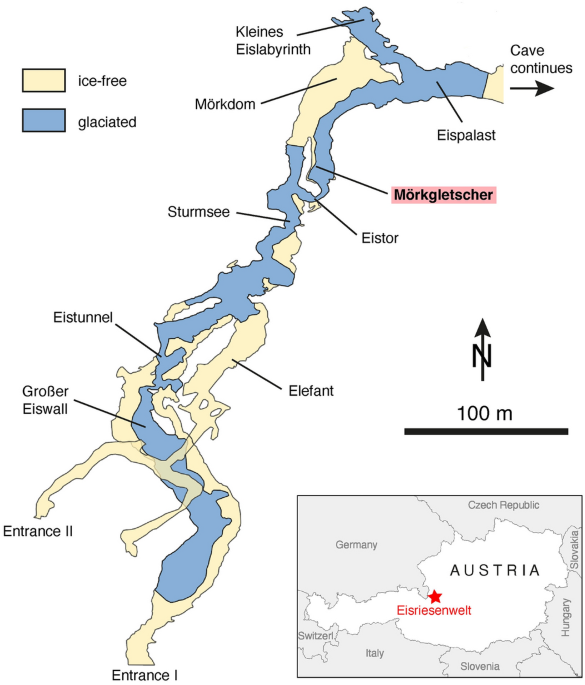

A special feature of the CCC layers at Mörkgletscher is their varying thickness and their lateral discontinuity. Both indicate that the thicker layers in particular were not deposited in situ, but represent redeposition of CCC. Our own observations made in winter in the ice-bearing part of Eisriesenwelt showed that fine CCC are being released from ice surfaces due to sublimation, forming tails of white to light brown powders. Similar observations were reported from ice caves in the Canadian Arctic where sublimation released CCC disseminated in ice, forming CCC deposits up to 5 cm thick24. These fine powders can be transported by the cave wind, which in Eisriesenwelt can reach more than 10 m/s on cold days in areas of narrow cross sections. It is interesting to note that cavers who explored and surveyed the cave about a century ago reported “flour-like dust often in finger-thick layers” at a narrow squeeze known as Sturmsee36 (this narrow passage had to be overcome by crawling and was later artificially widened; Fig. 1). These deposits were likely re-worked fine CCC deposited in the lee of this formerly strongly ventilated squeeze. A similar setting likely gave rise to the CCC layers at Mörkgletscher, located in the lee of another squeeze called Eistor (Fig. 1). Back in 1913, the first explorers had to crawl through a narrow gap between the ice and the rock ceiling to enter the hall called Mörkdom (Fig. 1) which hosts Mörkgletscher37. It is thus likely that these fine CCC had formed slightly further west (i.e., closer to the cave entrance) and became released from the ice by sublimation as a result of cold winter air being drawn into the cave through the main entrance. This hypothesis could also explain the fact that the CCC layers pinch out laterally towards the east, i.e., leeward from the former Eistor squeeze. Angular blocks of limestone embedded in some of the thickest CCC layers (but absent in clean ice above) represent breakdown from the ceiling, likely as a result of strong cooling and frost shattering. The thicker CCC layers therefore likely represent microhiatuses reflecting anomalously cold winter conditions giving rise to strong sublimation and short-distance eolian transportation of fine CCC and redeposition behind narrow passages followed by burial by younger layers of ice. There is no evidence, however, that the thicker CCC layers mark major (long lasting) episodes of ice retreat. The presence of the CCC layers marking microhiatuses therefore indicates that the mean rate of ice accumulation in the lower part of the profile was likely lower compared to the middle and upper part, where CCC layers are rare, thinner and can only be traced laterally for less than a few meters.

The ice cliff of Mörkgletscher did not exist in 1913, when the ice body extended all the way to the opposite cave wall. By about 1925, a 2 m-wide gap had opened due to ice sublimation37, which since then has widened to almost 8 m, exposing the internal structure of this floor ice and its CCC layers. The average rate of ice wall retreat due to sublimation during the cold season (plus a smaller contribution of summer melting) was about 6 cm per year.

Radiocarbon and 230Th constraints on the age of the CCC layers

Although the (thicker) CCC layers in the lower part of the ice section likely mark microhiatuses, they are nevertheless the key to obtaining quantitative information on the age of the surrounding ice. The purity of the CCC samples in terms of detrital contamination and the replicated samples are strong arguments that the overall decrease in conventional radiocarbon ages with increasing distance from the base of the section reflects an age gradient of approximately 2400 14C years, using the youngest radiocarbon age of each layer (Fig. 5). To constrain the timing of the start and end of ice accumulation, the radiocarbon dates must be corrected for the effect of dead carbon, followed by calibration to calendar years.

The dead carbon effect was assessed using radiocarbon analyses of modern CCC and DIC and compared to less precise constraints provided by 230Th dating. The radiocarbon dates of two modern CCC samples formed in the nearby Eispalast (356 ± 20 BP and 511 ± 19 BP) differ somewhat, reflecting the different water sources used for the two freezing experiments33. Such small radiocarbon variabilities of DIC are not uncommon in caves38,39. The value of DIC of one of the waters (395 ± 42 BP) is consistent with the CCC formed from it (356 ± 20 BP; the second water was not analyzed). We used the mean of all three measurements and its standard error (421 ± 17 BP) to correct the radiocarbon dates of CCC samples from Mörkgletscher. This approach assumes that the dead carbon effect has remained constant during the past few millennia. This appears justified because major changes in the composition and bioproductivity of the thin and patchy soil present above this part of the cave and of water–rock interactions in the vadose zone above the cave are unlikely in this time frame. This also includes land use changes which can be ruled out for the steep and rocky terrain above the cave. The resulting dead carbon-corrected dates were then converted to calendar ages using IntCal2040 (Fig. 6). The final ages are plotted on Fig. 6 together with the proposed age model which is constrained by the youngest ages of each dated CCC layer. The rationale behind this is the following: Several processes may result in calibrated radiocarbon ages being variably older than the “true” age. These include (a) contamination by detrital carbonate, (b) a higher dead carbon fraction, and/or (c) reworking of CCC derived from older ice strata. On the other hand, processes that would result in anomalously young CCC ages such as contamination by younger CCC or organic matter can be ruled out. The proposed linear age model is constrained by the youngest ages of each CCC layer following the rationale outlined above. A more accurate and precise depth-age model is currently not possible given the nature of the radiocarbon dates of such CCC samples (which represent maximum age estimates) and the limited number of CCC layers. The validity of our proposed age model, however, is confirmed in the upper part by a 230Th age whose 2σ uncertainty almost overlaps with the age model (Fig. 6). The 230Th age obtained from the deepest CCC sample is imprecise but still provides an independent age control, and it is consistent with the age model even within its 1σ uncertainty range (Fig. 6). The third 230Th age is unfortunately too imprecise to be used.The proposed depth-age relationship assumes that no melting had occurred at the base of this ice body. Basal melting would remove older ice and hence truncate the stratigraphic record. This process has been documented in some ice caves (e.g.9,41), but several lines of observations suggest that it does not play a significant role in Eisriesenwelt. (i) In all places in the cave where the contact between the basal ice and the rock or gravel beneath is well exposed, there is no macroscopic evidence of melting (based on observations during all seasons, but primarily during summer and autumn). If cave ice reaches the melting point it changes in crystal fabric resulting in a honeycomb-shaped structure (known as Wabeneis42). Such features were locally observed at the surface of ice stalagmites in late summer but were never observed in the basal ice. (ii) Ice temperature profiles obtained in Eispalast recorded negative temperatures year-round in the deepest ice layer at 7.3 m depth close to the base of the ice (unpublished data by the authors). Also, an earlier study of ice temperatures at Eispalast based on temperature profiles found no evidence of basal melting29. (iii) There is no evidence of measurable ice movement in this cave (due to basal sliding), even in parts where the ice forms steep slopes. This is based on decadal-long observations by the show cave personnel (pers. comm. A. Rettenbacher). If there had been ice movement, fortifications for the tourist trails drilled vertically into the ice slopes would have been deformed and/or tilted, which was not observed. This argues for the ice being permanently frozen to the rock or gravel substrate. In some exposures ice strata are inclined and change their dip laterally, mimicking folding. This structure, however, is not related to ice folding, but reflects the growth structure of large ice stalagmites and their variable internal stratification when exposed along an ice tunnel or cliff. In summary, there is no evidence of basal melting in Eisriesenwelt. During colder climate periods such as the Little Ice Age basal melting was thus even more unlikely.

Figure 6

Radiocarbon ages of fine CCC samples from the Mörkgletscher ice cliff corrected for a constant reservoir age of 421 ± 17 14C years and calibrated, showing median ages and associated 2σ uncertainties. The two yellow-green data points are 230Th ages with their 2σ uncertainties. The thick dashed red line is the proposed depth-age model based on the youngest ages of each sampled CCC layer.

Implications for long-term changes of the cave ice mass balance

The proposed age model suggests that ice accumulation at Mörkgletscher commenced about 3.2 cal kyr BP and terminated at about 0.2 cal kyr BP. The age model suggests a mean accumulation rate of 0.25 cm per year during the first two millennia until about the thirteenth century AD, followed by a mean rate of about 0.79 cm per year in the subsequent six centuries. This overall increase in growth rate is consistent with the scarcity of CCC layers (and the lack of thick CCC layers) in the middle and upper part of the section. In contrast, the abundance of CCC layers in the lower part suggests repeated episodes of intensive ice sublimation (possibly also minor ablation), hence overall lower accumulation rates, but still an overall positive ice mass balance.

The onset of ice accumulation at Mörkgletscher around 3.2 kyr BP may have been related to an episode of glacier advance in the Alps, known as the Göschenen 1 advance and more recently called Iron Age Advance Period 1, starting around 3 kyr BP43. The change towards a higher mean accumulation rate during approximately the thirteenth century AD occurred at the onset of the Little Ice Age, which started in the Alps around 1260 AD and ended at about 1860 AD44. In addition, the end of the ice accumulation phase—based on extrapolation (Fig. 6)—falls at the end of the Little Ice Age. In the 1920s, the ice had started to retreat from the southern cave wall and already exposed part of the Mörkgletscher ice cliff, i.e. the mass balance in this inner part of the show cave had become negative by then. Since then, the ice cliff has retreated by about 6 cm per year.

We also tested the CCC-dating approach in two other parts of Eisriesenwelt and briefly report here preliminary results. First, we applied this approach to Eispalast (Fig. 1), where an ice core drilling had encountered 7.3 m of ice20. We re-drilled this ice body and sampled a CCC layer at 3.2 m depth (sample F320, 3955 ± 23 BP). Using the same correction for the dead carbon effect as applied above, the calibrated age suggests that this ice is not more than 3.9–3.7 cal kyr BP old (2σ range, Table 1). Whether the basal ice is about 5 millennia old as suggested by imprecise radiocarbon data of particulate organic matter20 remains an open question.

Secondly, we sampled fine CCC layers in a place called Eistunnel, which is a tunnel that was artificially cut through the ice in the middle part of the show cave in 1963 (Fig. 1; pers. comm. A. Rettenbacher) and which has since widened substantially by sublimation. Multiple layers of fine CCC are present in this ice whose gravel base is well exposed. A sample from a CCC layer about 45 cm above the ice base yielded a radiocarbon age of 1046 ± 20 BP (sample ETB). When corrected for the dead carbon effect the same way as the Mörkgletscher samples, the calibrated age is 653–553 cal yr BP (2σ range, Table 1), which suggests that this ice was likely formed between about the fourteenth and fifteenth century, assuming that no ice was lost due to basal melting. As detailed above for the Mörkgletscher site, basal melting does not play a significant role in this cave today. Given the more proximal location of Eistunnel with respect to the lower cave entrance, basal melting is even more unlikely there compared to Mörkgletscher. In essence, this CCC age falling into the Little Ice Age implies that the central (and likely also the frontal) part of the show cave may have been largely ice-free during medieval times. The observation that older ice is preserved in the inner part (Mörkgletscher, Eispalast) is in contrast to what would be expected from the point of maximum winter cooling (more pronounced in the near-entrance part). Part of this discrepancy may be explained by (i) more pronounced ice sublimation in the near-entrance part due to a greater temperature difference, (ii) the presence of large depressions in the inner part allowing thick and less vulnerable floor ice deposits to form compared to the more proximal parts that are characterized by steep slopes, and (iii) local ingress of water. Today, large ice stalagmites form in the cooler parts of the cave close to the entrance due to the drip water, while water entering the inner parts of the ice cave mostly forms sheet-like deposits (unless artificially diverted).

The fact that the ice at Mörkgletscher has been retreating for about a century suggests that the current warming has already penetrated deeper into the cave than during the Medieval Warm Period. In this context, it is important to mention that the cave’s microclimate has been artificially modified for about a century by closing the lower entrance with a door during the warm season (to prevent the cold cave air from escaping). Old surveys indeed shows more ice in Eisriesenwelt during the 1950s and 1960s compared to 192032. Without this door, the summer cave temperatures would be higher, the near-entrance part of the show cave would most likely be ice-free (only seasonal ice) and the ice deposits in the inner ice parts would probably become increasingly vulnerable.

Perspectives

Radiometric dating of congelation ice remains a challenging task, which ultimately limits attempts to unravel the full potential of this poorly understood paleoenvironmental archive.

Given the wide-spread lack of organic matter in this type of cave ice (and the challenge to constrain soil and karst reservoir effects), the use of fine CCC as a chronometer seems an attractive way forward. In terms of radiocarbon, two aspects are important. First, radiocarbon dates of CCC are maximum age estimates and the accuracy of the final age hinges on the magnitude of the local dead carbon effect. Secondly, fine CCC disseminated in ice and thin CCC layers likely formed together with the surrounding ice. In contrast, thicker CCC layers represent microhiatuses and require sublimation of pre-existing CCC-bearing ice followed by short-distance transportation by cave wind to accumulate in such a concentrated manner. The issue of the dead carbon effect could be tackled by a systematic DIC study of modern cave water, but we are unaware of such a kind of study in ice caves. Depending on the size of the cave, the thickness of the rock overburden, the types of water pathways, and the structure of the soil, it is likely that such a study would yield a range of values for the dead carbon effect, probably also on a seasonal scale. Applying such a modern average correction factor to millennia-old ice requires independent age control. This is why 230Th data of fine CCC would be highly valuable. Given their very large surface area, the delicate CCC crystals and crystal aggregates are inherently less pure with respect to detritally bound initial 230Th than regular speleothems such as stalagmites. Attempts to purify fine CCC samples by repeated washing in an ultrasonic bath and hand-picking of contaminant particles under a binocular were only partially successful as shown by the still very low 230Th/232Th ratios (Table 2) resulting in large corrections. A way to obtain more accurate dates of fine CCC is whole-sample dissolution and isochron methods in order to distinguish between isotope ratios of the detrital and the authigenic phases45. This requires extra laboratory effort and cannot be done for many samples, but would provide a few important anchor points against which a radiocarbon-based ice stratigraphy could be compared.

Finally, there is a novel radiometric technique emerging which utilizes the very rare noble gas 39Ar radioisotope, trapped in ice during its formation. The half-life of 39Ar is 269 years, permitting the direct dating of ice as old as about two millennia46. In a test study, 4.2–6.7 kg samples of ice from the base of two glaciers in the Tyrolian and the Swiss Alps were analyzed. Though the results are encouraging they are associated with substantial measurement uncertainties, e.g., 1126 + 1286/− 273 years in the case of the oldest of these samples, which involved counting 31 atoms in 20 h47. Five cave ice samples were analyzed for the abundance of 39Ar from Leupa Ice Cave located in the Julian Alps of northern Italy. The results also show large analytical uncertainties48. Although 39Ar measurements are currently performed by only few laboratories worldwide and are very time consuming, major improvements in count rate (F. Ritterbusch, pers. comm.) hold reasonably high promises that congelation ice of the common era can eventually be reliably dated using this technique.