Japanese scientists have made a groundbreaking discovery. You have identified a covalent bond between two carbon atoms that share only one electron. “This (research) was motivated by curiosity to understand where the limits of chemical bonding lie,” says Takuya Shimajiri of the University of Tokyo.

One-electron bonds were first proposed by Linus Pauling in 1931, and bonds between heteroatoms have been reported ever since. However, no direct evidence for their presence between carbon atoms had been observed so far. “We came to the idea that this is possible with appropriate molecular design,” says Shimajiri.

The sharing of electron pairs serves an important purpose. Electron pairs fill the outer shell of an atom with electrons, making it more stable. If one important electron is missing, the one-electron bond is naturally much weaker and therefore breaks more quickly. Therefore, they are only proposed to exist temporarily as intermediates in chemical reactions.

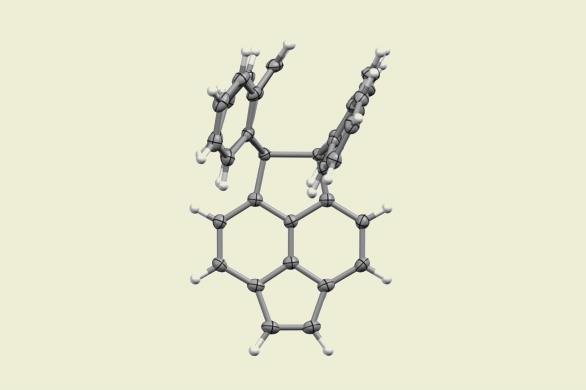

“To address this problem, we adopted an intramolecular core-shell strategy in which weak bonds (core) are protected by surrounding them with a hard π skeleton (shell),” Professor Shimajiri explains. The stabilizing skeleton is composed of electron-rich hexaphenylethane derivatives that lose electrons during oxidation reactions to form charged carbocations and radicals.

Although two electrons are lost during this oxidation, resulting in the production of two triarylmethyl cations, the reaction occurs so quickly that it is considered a “one-step” reaction. However, the researchers reasoned that if they could control the sequence of steps, they could capture the carbon radicals that form when the carbon-carbon bonds within the hexaphenylethane molecule break during the reaction. This cleavage creates a carbon atom with an unpaired electron that, under the right conditions, can be shared with an adjacent carbon and stabilized by the rest of the molecule, an elusive one-electron bond. may form.

To achieve this, the scientists took advantage of the elongated carbon-carbon bonds in hexaphenylethane, caused by the bulky aryl group attached to hexaphenylethane. This stretching changes the electronic properties of the molecule and makes the energy gap between the orbitals of the important intermediate large enough that the reaction no longer occurs as quickly. Instead, it can slow down to a stepwise mechanism that allows carbon radicals to be captured to form one-electron bonds.

“The strategy involves … stretching the bonds of the parent molecule and adjusting the energies of the molecular orbitals,” says Kate Ansteter, a researcher at the University of Edinburgh who was not involved in the study. “This is a true testament to elegant chemical engineering.”

“Combining synthesis and spectroscopy, computational chemistry and centuries-old theory is an elegant example of what can happen when different subfields of chemistry have a common synergy.” added Philip Camp of the University of Edinburgh, who was not involved in the study.

This new bond also challenges our fundamental understanding of what exactly constitutes a covalent bond. “Roughly speaking, this bonding is caused by the proximity of the atoms to the rest of the molecule, not the other way around,” Camp says. “It has not been proven that it meets the (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) definition.”

But Shimajiri says this is the important point. “Our goal is to clarify what a covalent bond is and, specifically, when a bond is considered a covalent bond and when it is not. It’s about exploring a wide range of undiscovered bonds, not just between atoms, but between all elements.”

“While there are other examples of this binding motif, this study in particular has the potential to open up new areas of research because the bond is between two carbon centers,” says Ansteter. “Carbon is ubiquitous in the known universe, so teaching this element new tricks will spark interest in a wide range of research fields, from fundamental theory to applied materials.”